Professor Harris’ research on monetary sanctions in Washington was cited in this powerful Seattle Times editorial published yesterday:

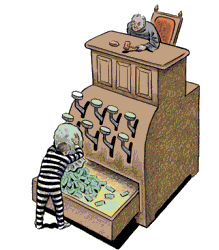

THIS is how a modern-day debtors’ prison works.

You are convicted of a felony drug offense. As part of a two-year prison term, a judge imposes $2,300 in fines and fees, without taking into account your ability to pay.

A 12 percent interest rate begins ticking when the gavel drops. The bill keeps right on growing through the prison term; by the time you get out, $600 in interest has been added to the balance. By then, the debt is being handled by a collection agency, which imposes its own fees. Additional fees include paying by credit card, for paying in installments and for missing payments.

If you lose your job, or prioritize feeding your kids over paying the court fines, you face one extra hazard if you happen to live in Benton County: being sent back to jail, or being sent to work on a work crew — at a cost of $5 a day, cash.

Read the full editorial at the Seattle Times

“Do the crime, pay the fine.” A little different, right? Many are unaware that when convicted of breaking the law, not only do people “pay” for their crimes by doing time, but they are also forced to pay up financially. The costs include court processing, defense attorneys, paper work, and anything else associated with their incarceration and supervision. In fact, anyone convicted of any type of criminal offense is subject to fiscal penalties or monetary sanctions. (If you have ever paid a traffic ticket, for example, you have paid a monetary sanction.) Further, the base fine of, say, a speeding ticket or even a major criminal conviction is just a small portion of the total cost. There are fines, fees, interest, surcharges, per payment and collection charges, and restitution. Until these debts are paid in full, individuals who have otherwise “done their time” remain under judicial supervision and are subject to court summons, warrants, and even jail stays.

“Do the crime, pay the fine.” A little different, right? Many are unaware that when convicted of breaking the law, not only do people “pay” for their crimes by doing time, but they are also forced to pay up financially. The costs include court processing, defense attorneys, paper work, and anything else associated with their incarceration and supervision. In fact, anyone convicted of any type of criminal offense is subject to fiscal penalties or monetary sanctions. (If you have ever paid a traffic ticket, for example, you have paid a monetary sanction.) Further, the base fine of, say, a speeding ticket or even a major criminal conviction is just a small portion of the total cost. There are fines, fees, interest, surcharges, per payment and collection charges, and restitution. Until these debts are paid in full, individuals who have otherwise “done their time” remain under judicial supervision and are subject to court summons, warrants, and even jail stays.